|

Physicians treat the afflictions of people; biomeds treat those of medical equipment. Both roles are key to maintaining a safe, effective, and economically efficient health care organization. Occasionally, however, biomeds do not feel the love that physicians do. “Sometimes, we don’t receive the respect that is needed in our profession,” one respondent writes in response to 24×7’s 2008 Compensation Survey.

So, some biomeds demand it—or at least ask nicely. “I’m looking to ‘create’ a niche with IT/biomed work at my hospital, hopefully creating a new title with better pay,” another respondent writes.

To achieve improved job satisfaction, both biomeds quoted above will require a benchmark to judge their compensation against those within the market. In general, satisfaction rises with salary, and this year’s survey bears that trend out again.

The survey also covers salary ranges, benefits, training, workload, and job satisfaction. This year, 1,733 people responded to the survey in its entirety, a slight 6.9% increase over last year. The good news: The data shows slight improvements in salary, workloads, and satisfaction. The bad news: Many biomeds still believe that levels of both compensation and respect could be a little higher.

Reflecting both sides of the coin, one female biomed from Wisconsin writes, “I can’t think of any profession that has such varied work responsibilities. We have to be both detail oriented and see the bigger picture. Clinical engineering has a reputation for finding the answer and following through. That garners a measure of respect that hopefully will get us ‘out of the basement.’ After more than 16 years as a biomed tech, I am not at all bored. I still enjoy coming to work and feel blessed that I have found my niche.”

Money Talk

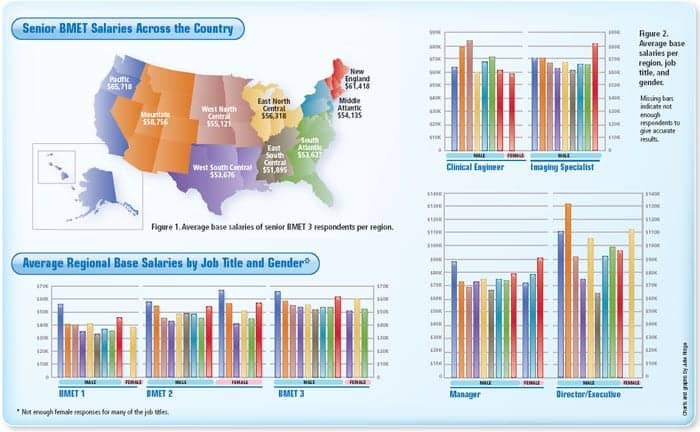

Though many do describe the biomed profession as a niche, that niche incorporates a lot of diversity, which is reflected in the reported compensation. The average salaries of survey respondents range from $35,000 for a 20-to-25-year-old BMET 1 to $95,000 for a 51-to-60-year- old specialist. Throughout the country, BMET 3s represent the largest number of respondents, with their salary ranges displayed in Figure 1.

|

| Click on image for larger view |

Once again, the Pacific region leads the country in salaries, paying BMET 3s an average salary greater than $65,000 while the East South Central Region trails with an average salary just below $52,000. In all regions, the reported salaries increased slightly over last year, from as little as half a percent in the Pacific to 7.5% in New England. To some biomeds, however, the raises come too slowly. One respondent writes, “I feel that our field deserves more recognition in the way of compensation. Other technicians and the nursing staff have enjoyed much larger increases in salary the past 10 years or so. We have stagnated.”

|

Stand Up and Be Counted

Compensation is often depressed by the economics of health care. “Between outsourcing and the health care facilities trying to save a dollar, we constantly need to show the value we add to the facility,” one respondent writes. “Heath care facilities are being driven to the bottom line and sometimes overlook what their actual needs are. I have been on both sides—in-house and ISO—and the best way to keep satisfied customers is good communication skills and quality work.”

Although many biomeds may bounce between in-house and ISO opportunities, the majority of respondents work in hospitals and medical centers (see Figure 3). Other less obvious opportunities include pharmaceutical manufacturing clinics, CMMS software companies, consulting organizations, corporate headquarters, equipment rental and repair firms, federal procurement organizations, HME dealers, hospital equipment rental companies, imaging centers, and dialysis clinics, with the survey showing that 2% of respondents work in facilities such as these.

Opportunities generally open with more education. “I’ve been in the field 47 years, and I have seen many, many changes since my initial ‘repair everything’ training. Many specialty and advanced courses along with manufacturers’ training have made it a very dynamic job. It has evolved and specialized so much so that there is plenty of room for growth and upward mobility,” one biomed writes.

Business training may be as valuable as biomed training. Professionals with MBA degrees report the highest average salary at nearly $89,000. Yet, only 27% of the respondents report that they are pursuing formal education.

|

Gender matters too, although not as much as in the past. Like last year, the majority of respondents—92%—were overwhelmingly men, but the number of women who responded did rise by a small amount, from 6% to 8%. In some areas, the average salary for female biomeds has surpassed that of men: Female BMET 2s earn more money on average than their male counterparts in the Pacific, Mountain, East North Central, and New England regions. However, women still have a path to forge: In many areas, there were not enough female respondents to calculate an accurate statistic.

Perking Up Compensation

Compensation, however, is not all about salary. It also incorporates typical benefits, such as health, dental, and life insurance, as well as perks that fall within the “other category,” such as a car allowance or mileage reimbursement, credit unions, legal assistance, flexible schedules, pharmacy discounts, paid time off, bonuses, stock options, fitness club memberships, pensions, 401K/403(b)s, cell phones, laptops, and disability.

Almost one-third of respondents, or 29%, cite benefits of this sort that comprise another $2,501 to $5,000 in compensation. One-fourth (24%) cite this compensation as $1,000 to $2,500, 12% say it makes up an additional $7,501 to $10,000, and 10% add more than $20,000 in such perks. Smaller percentages round out the remaining ranges.

Salary Satisfaction

When biomeds consider their compensation, are they happy? Generally, satisfaction climbs with salary. This is true of both sexes, although women have a higher tolerance for lower wages: The average salary of a female biomed reporting the lowest level of satisfaction is $44,902 versus men in the same category who report earnings 4% higher, at $46,761.

|

A female biomed in Ventura, Calif, reflects this tolerance, writing, “It is a wonderful profession to be a part of, very rewarding and good benefits.”

Perhaps not surprising, respondents lower in the career hierarchy (and therefore receiving less compensation) tend to report greater levels of dissatisfaction than senior biomeds. Eight percent of BMET 1s and BMET 2s report being very unsatisfied with their compensation versus 3% of imaging specialists and managers.

Similarly, 8% of BMET 1s report being very satisfied with their compensation versus 27% of directors/executives. This difference may be understandable: Very satisfied BMET 1s earn a rough average of $58,000 versus $104,000 for very satisfied directors/executives, a nearly 80% difference.

Though the majority of respondents report being neutral or satisfied with their compensation relative to their education and experience (see Figure 10), some do believe they are not recognized for the diversity of knowledge and tasks they undertake. “BMETs are not regarded as a valued source despite being people that are essentially part maintenance, part IT/network/PC repair, and part nurse by having to know how the devices interact with patients,” one biomed writes.

Others focus on the value of their work rather than salary. One biomed writes, “We can complain about being undercompensated for the responsibility the profession demands, but it will always provide a rewarding, if not exhausting, challenge.”

Overworked or Underworked?

Workloads can be exhausting, but, compared to last year, they have eased a little. This year, 68% of the respondents believe their workloads are acceptable, versus 64% last year. Yet it is still more work than in 2006, when 73% of the respondents believed their workload was manageable.

Many respondents do note that workloads are cyclical, and hiring needs can impact tasks and schedules. “I have the latitude to adjust scheduling,” one Florida supervisor with 16-plus years of experience says.

Others believe that more staff—and this year quite a number of respondents stress in particular qualified staff—would help to ease workloads that are increasing due to expanding hospitals, inventories, and responsibilities. “Our responsibilities and workload keep increasing, but we haven’t added any staff,” a New York-based BMET 3 with a bachelor’s of science degree writes. He adds that his department keeps picking up more physician’s offices for repairs and preventive maintenance, which means more travel and repair time.

Additional staff can also reduce the number of hats worn by any one team member, particularly the manager. One Southern California manager with more than 11 years of experience notes it is “hard to be a tech and a manager at the same time.” Some complain of having to care for nonmedical equipment, such as laser printers, fax machines, and pillow speakers.

|

“When are hospitals and the industry going to wake up and realize that we are a special breed? No other department in the hospital has such a cross section of knowledge, from electronics to plumbing, to IT. We are required to interact with staff on every level in most departments,” one survey respondent writes.

A clinical engineer in the East North Central region suggests that workload could improve by “defining departmental responsibilities more clearly.”

This year, quite a few respondents say technology could also help ease the workload. A biomed manager in Nevada writes that “going paperless in the long run” would help.

A CBET at a hospital in Ohio agrees, saying, “Laptop computers and electronic PM close-outs. Way too much paperwork!!!” And from a CBET at an ISO in Texas with 16-plus years in the profession: “Another full-time engineer or shared full-time engineer. Move more away from older test equipment and into the automated test equipment. Use improved technology to reduce time spent on paperwork.”

Even though many say they need more help, 64% of respondents report that at their place of employment, no full-time biomed positions are currently open. Those who are looking to hire may have difficulty finding qualified people. One CBET with more than 11 years in the field notes, “We cannot find experienced people to fill open positions, and we have too many new people with not enough time to both train them on the job and do our jobs as well.” He suggests better pay would draw more qualified applicants, but that “hospitals do not want to pay for performance and education up front.”

Another experienced biomed, this one in Rhode Island, states, “I feel we can do more services for the hospital and save more money if we were able to pay more money for more qualified people. They need to send us for more training, and they could also hire another person to take on beds and other minor equipment and tasks that seem to take us away from our more important roles in the hospital.”

Gravy Training

Though many agree that training can contribute to a more effective biomed team, nearly one-third (29%) of respondents say they have not received any technical training in the past year, more than any other category. “I have not received any service training, yet am expected to service high-end units such as CT and CV/angio fluoro units,” one biomed says.

|

About one-fourth of respondents had 21 to 40 hours of technical training over the past year, 16% had 41 to 80 hours, and 11% had more than 80 hours. Ten percent and 9% reported 1 to 10 hours and 11 to 20 hours, respectively. One-third also reported various hours of managerial training.

Information about the profession is also gleaned through sources such as magazines, the Internet, meetings and conferences, journals, vendors and tech manuals, and networking. Magazines remain the most popular method with 37% of respondents reporting they read them, but the Internet is closing fast at 35%. Last year, about 29.5% of respondents went online for professional information. Respondents use the remaining sources above in the order listed.

Of course, the value of on-the-job and cross training cannot be discounted. “We basically learn on the job. Service schools are not much of an option to learn about medical equipment. We depend upon experienced technicians or manuals, and sometimes we’re lucky and a manufacturer salesperson gives in-service training on new equipment,” a respondent writes.

Biomed Advocates

Despite the negatives, however, most biomeds—a whopping 89%—would recommend their profession to others. This is slightly more than last year’s 87% but less than the 91% of respondents who replied with a positive recommendation in 2006.

These percentages can have an impact on the growth of the profession. As members of the industry approach retirement age, and many are in that range, it will be more difficult to replace talent if the field does not promote itself more positively. “I don’t see many young people looking toward the career. It’s hard to find new folks that want to train in biomed and not IT,” one respondent writes.

|

The disadvantages to overcome include the perceived lack of respect and adequate compensation as well as an organizational focus on money rather than patient care. Compensation complaints range from “low compensation for the expectations” and “not enough money for the responsibility” to being “considered overhead, like maintenance.”

“There needs to be a grassroots effort by clinical engineering organizations to promote our field within the hospital setting,” another biomed writes. “The hospital realization that clinical engineering can be a clinical asset both in the day-to- day operations as well as with new technology will promote an environment that will stimulate both professional and personal growth.”

In addition, many believe the shops could be run better. “Too much big business taking over. All I hear now is ‘make us money’ at the hospital’s expense—instead of ‘provide the best service possible at the best cost possible,’ ” one respondent writes. Another respondent, a BMET with 6 to 10 years of experience, states, “The department is run by bean counters, not knowledgeable biomedical engineers.”

Many biomeds get into the field because of their desire to help people, and therefore find reward in the care that they deliver, albeit indirectly. Other pluses include the variety, challenge, opportunity to learn new technology, and stability. One Pennsylvania biomed with 16-plus years of experience writes, “Every day is an adventure.” Other comments include a “noble profession,” “a great sense of accomplishment helping others,” and “the best way to impact the most lives.”

A female biomed working at an OEM in Illinois sums the advantages up nicely, writing, “It’s dynamic, challenging, and rewarding. There are opportunities to meet and interact with quality practitioners, investigators, and help patients heal.” And that is definitely priceless.

Renee Diiulio is a contributing writer for 24×7. For more information, contact .

|

Additional Tables

Salary by Satisfaction with Compensation by Job Title (PDF, 38 KB)

Salary by Satisfaction with Compensation by Gender (PDF, 26 KB)

Salary by Job Title by Years with Employer (PDF, 18 KB)

Salary by Job Title by Age (PDF, 16 KB)

Salary by Job by Number Years by Region (PDF, 23 KB)