The Compensation Survey for 2009, in some ways, revealed just how harsh the economic downturn has been for the biomedical field, and also illuminated the challenges and rewards experienced across the nation by biomedical equipment technicians, clinical engineers, managers, and others in the profession. Whether working in a hospital, clinic, imaging center, or for an OEM or consulting company, biomeds are being called on to perform more duties with less resources than ever before.

“Too much is expected in a field where you can’t take shortcuts,” said one 16-year hospital veteran.

And while biomeds would like to see some sweeping changes in compensation, training, and workloads, a surprising number would like to see significant changes in what might seem like lesser issues: more administrative and clerical help, a need for more even work distribution among department members, and a reduction of nonessential preventive maintenance (PM) projects.

|

|

“Current economic times are stressing hospitals greatly; many, such as ours, have reduced training and travel in an effort to save money,” said one biomed. “I am afraid that the in-house biomedical staff is being reduced to PM techs simply because it is less expensive to have lower-level technicians than to build and promote better technicians to serve a more proactive role in the facilities.”

The survey also revealed other surprising, and not so surprising, results: Managers and specialists felt they were more frequently pulled into biomed tasks, preventing them from doing their own jobs, which causes frustration. Many also said they would like more opportunities to hire vacation coverage and hire less experienced or part-time biomeds to conduct PMs, and would like better inventory control procedures in place.

This year, many respondents also reported that the increased workload due to the expansion of facilities and the increase of devices on the docket has led to a true need to increase their workspace, and they would like to see the issue addressed and vital workspace expanded.

The 2009 Compensation Survey covered a variety of areas and issues, including salary, benefits (and the satisfaction associated with both), workload and job satisfaction, training, and advocating for the profession. This year, 1,641 readers responded to the survey, a slight decrease from last year’s 1,733. Men made up 93% of the respondents, and BMET 3s represented the largest number of respondents.

Money, Money, Money

Salary comparisons between men and women are difficult to calculate because of the lack of female response to the survey. However, as the chart (See Figure 1) shows, biomeds across the nation tend to be well compensated. In an interesting twist, one female biomed noted that she entered the biomedical field precisely because it was male-dominated: “I entered the industry once I realized it was saturated with men, which usually equals decent pay.” Still, on average, the survey showed the average salary for women to be $57,934, while the average salary for a male in the profession came in at $65,770.

When it came to additional compensation—overtime, for example—28% reported receiving between $2,501 and $5,000 additional compensation, while 11% reported more then $20,000. In addition to pay, 3% of respondents reported receiving other benefits, such as cell phones, computers, bus passes, gym memberships, community charity matching, long- and short-term disability insurance, and event tickets. One biomed even considered a steady paycheck a benefit.

Overall, those in the higher salary range tended to be happier with their compensation. For instance, women who said they were “very satisfied” had an average salary of $70,894, and those least satisfied had a salary of $42,618. Men fared better in average salaries over women, and those saying they were most satisfied made, on average, $77,158, while men least satisfied with their salaries made an average of $58,103.

|

|

|

|

|

In terms of response toward salary and benefit satisfaction, comments ranged from the positive to the negative. Many comments echoed one biomed who said, “The reason I am in this game is because I love what I do in helping humankind, not for the money.”

However, many respondents also reported the dampening of salaries and other benefits, due to the economy, which they felt made for an overall less satisfying job experience. Said one CBET/CRES, “I don’t think we are compensated for the skills, stress, and hazards as well as others that are in semirelated fields.”

Pay discrepancies, as they related to years of service, were also highlighted, with one senior tech saying, “Unfortunately for me, the junior techs are earning as much as I am, but are much less productive.”

Pay discrepancies can and do exist. However, varying costs of living throughout the country can be a big reason, as one manager explained: “Read this survey and become informed, but don’t use it as an excuse to walk into work one day and say that you deserve a raise because someone in Boston is making almost twice as much as you are in rural Idaho,” he said. “If you look at a biomedical position as simply a job and a dollar amount, you will walk around missing the rewards that can come along with the profession.”

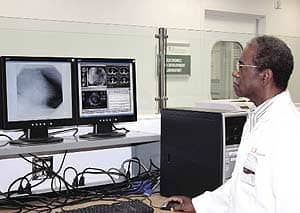

A Place to Call Home

For those that have a taste for variety, the biomedical field offers a diverse selection of workplace opportunities. Biomeds can be found working for software companies, consulting organizations, biomedical equipment rental and repair providers, equipment distributors and dealers, hospital equipment rental companies, imaging centers, clinics of various sizes, humanitarian and mission organizations, military contractors, support centers, asset management companies, blood banks, and research centers, as well as working as educators at universities, colleges, and technical institutes.

The need for highly trained and skilled biomeds is always present, no matter what the economic climate. In fact, a senior BMET reported that his hospital has been advertising for biomeds, “but we are not receiving any qualified resumes.”

Only 4% of those responding said their facility had five or more positions open, while 74% said there were none. This does not necessarily indicate a lack of need, as a few respondents commented that positions have been eliminated and will not be replaced in the near future.

Balancing Workloads

In a surprising uptick, 69% of respondents reported that their workload was acceptable, compared to 64% 2 years ago. And 2 years ago, 36% reported their workload was not acceptable, but this year, that number dropped to 31%, despite the current economic conditions.

Those reporting acceptable workloads cite an even division of the workload among their teams, and administrators and managers who, they said, understood what’s involved in having a balanced work environment. Others felt their current work balance was fine—as long as staffing levels remained unchanged. A growing number said yes, but it’s bordering on no as more work is added.

One supervisor at an OEM pointed to an increased workload as a means of more responsibility and welcomed the challenge. “An increase in my workload signifies an increase in responsibilities, trust, and viability within the department and the company,” he said. “A stagnant workplace hinders personal self-growth, which leads to job, and, ultimately, career dissatisfaction.”

Another CBET at a hospital in Oregon said, “Our workload is managed by keeping teamwork in our shop as a top priority. Our workflow is maintained by keeping communication open within our department and between directors and managers of critical departments. Cross training is also an essential part of our completing all tasks in a timely manner.”

A female clinical engineer with a BS degree underscored the understanding of her director as a key factor in keeping workloads among her colleagues manageable. “There are always projects waiting in the wings for us to work on when we are ready,” she said, “but they are not assigned to us unless we have the time to take them on.”

One BMET III said, “The workload is actually lower now that we have adopted a more risk-based program.”

For those who felt their workloads were unacceptable, the most critical complaint was a lack of staff to meet the work demands. Many cited the expansion of services and facilities, without a corresponding increase in staff, as the culprit. A senior tech with an AAS degree said, “Equipment is added—without concern for service and workload when adding.”

In line with unacceptable workloads came the fear that quality is suffering. Said one CBET, “A recent reduction in workforce has forced us to do either the same amount or more with less. Quality suffers as employees become stressed about workloads.”

“There needs to be a more even distribution of workload between technicians,” said one CBET. “My workload is two or three times that of my coworkers, and I have a lot of high-risk items compared to them.”

The lack of qualified and fully trained technicians was also cited numerous times as a reason for unacceptable workloads, as more qualified techs feel they have to step in and finish projects. Administrative matters, such as checking e-mail, writing reports, and being asked to complete work outside the technical parameters of biomedical work, were also highlighted as adding to an unacceptable workload. Said one respondent, “We are tasked with solving problems, even if they are not ‘technically’ within our scope.”

Managers and supervisors also reported that they are increasingly tasked with taking care of managerial duties while simultaneously performing biomed duties.

A frequent complaint about workload satisfaction revolved around PMs. Said one CBET: “Some months there are hundreds of PMs assigned to me, and they are expected to get done, while keeping up with other repairs and projects.” Other comments suggested a better management of PMs; less regulation that does not benefit patient care, such as unnecessary PMs; and up-to-date PM procedures.

What could help ease the workload? Accountability came up a number of times. A CBET with more than 16 years of service said, “We spend an unacceptable amount of time repairing abused equipment. Our clinical departments do not have a budget for equipment maintenance. Clinical engineering absorbs it all, so there is no incentive to keep costs down by the users.”

Other suggestions included the use of automation systems, such as automated test equipment or wireless handheld devices for processing work orders, better test equipment, better medical equipment management software, and even, “Appreciation from my employer.”

The Impact of Training

Without question, ongoing training—and in many cases, certification—lie at the heart of being a skilled biomedical technician, clinical engineer, or manager, yet this year, 36% of the techs reported that they had no opportunity for training, up from 29% last year. Still, a combined 64% said they had received anywhere from 1 to 40 hours of training in the past year, lending credence to the belief that continued training is very important in the field. “Certification, as well as education, will ultimately get you to where you want to go in your career, as well as your compensation,” said one biomed.

Another echoed the sentiment, saying, “After 7 years, and gaining CBET certification, I am finally in a position that compensates me for my experience. Obtaining certification put me in a position to advance from a level one BMET to a level three within 2 years. My CBET certification made all the difference, and will open many doors for future employment, if needed.”

Others know the benefits and felt frustration with training cuts. “With the state of the economy the heath system has made several cuts, but training should not have been one of them!”

Managers didn’t fare much better, with 66% saying they did not receive any management training and 19% saying they received 1 to 20 hours.

Making time and finding the money for ongoing training can be a challenge. Managers and supervisors in the survey shared their disappointment regarding the time and resource constraints that prevent needed training, both for current and new employees.

“I believe the BMET field has become very diluted with BMETs lacking formal training,” said one biomed manager. “I’ve been to hospitals that were hiring equipment cleaning techs out of central supply to do BMET work, thinking on-the-job training would be enough. One cannot expect quality work from BMETs without formal training, and one cannot expect quality work from undermanned departments.”

|

Another biomed commented on the need for mandatory training: “I feel that people in this field should meet the same requirements that it takes to be a CBET candidate, and certification should be mandatory for all who repair any type of diagnostic or therapeutic medical equipment. This needs to be addressed at a national level.”

Outside resources can help members of the profession stay abreast of the field, with 33% receiving information from magazines and 17% from meetings and conferences. Information from the Internet has stepped up, with 39% getting their information there, up from 35% last year and 29.5% 2 years ago.

Many respondents commented on the need for a national organization for the profession. This national presence, many thought, would give more respect to the profession, provide vital continuing education opportunities, and, in essence, give an overall voice and direction to the biomedical field.

Advocating for the Profession

|

|

Despite the numerous comments about lack of adequate staffing, money, resources, and training, fully 90% of the respondents to the survey said they would recommend the profession to others considering the field. This percentage is up from 87% 2 years ago, and up from 89% last year. While these results may be surprising, many pointed to the learning opportunities, chance for advancement, and opportunity for income growth as key drivers in recommending the biomed profession. This enthusiasm for recommending the field could become increasingly important in the future, as older biomeds retire and the need for new people grows.

Respondents who would not recommend the field did so because they felt a lack of respect and felt they were overworked. Said one clinical engineer, who has worked at a hospital for more than 11 years, “We oversee just about everything electronically and mechanically related in-house, but we don’t get recognized for the job we do. We are the people who work behind the scenes to help the ‘show’ run, but no one knows what exactly we do on a daily basis.”

Being valued like nurses and physicians would be welcomed, according to many respondents. “We are viewed as an expense rather than an investment. When will we be seen, accepted, and appreciated, as we should?” said one.

Another called for more exposure to the outside world. “We need to let the world know what a biomed does and its importance in the health care world,” he said.

Still, many aligned with the respondent who said, “Thank you, for allowing me to take this survey. The questions had me recapture the reasons why I come to work every day—not just to provide for my family, but for the pleasure and exhilaration of helping others.”

Overall, most survey respondents felt the biomedical field was a great career path, in which working together toward the common good of patient care drives an overall sense of nobility, pride, and accomplishment at the end of each day. “Even with all of the challenges I currently face on a daily basis, the working conditions, compensation, and camaraderie that I share with my colleagues make the work enjoyable,” one biomed said.

Respondents also stated they were proud to be part of a field and work in organizations that are in the business of helping people and saving lives. They enjoy the variety of work and helping end users better understand the equipment needed to do their jobs well.

“It is a very satisfying career,” one biomed said. “At the end of the day, I feel that I have been productive, and, just maybe, my knowledge has helped in some way to save lives.”

Cynthia Kincaid is a contributing writer for 24×7. For more information, contact .

Additional Tables

Salary by Job Title by Age (PDF, 24 KB)

Salary by Job Title by Number of Years in the Field by Region (PDF, 36 KB)

Salary by Job Title by Years with Employer (PDF, 23 KB)

Salary by Satisfaction with Compensation by Gender (PDF, 14 KB)

Salary by Satisfaction with Compensation by Job Title (PDF, 23 KB)