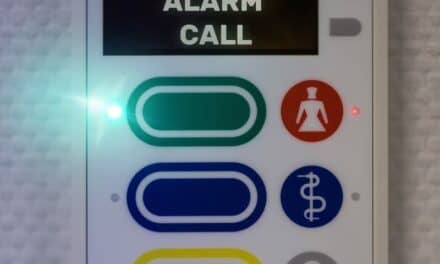

Taking the time to create purchase specifications will support the quest of finding and purchasing the right product with the required functions. (photo courtesy of Siemens Healthcare)

Through the years, the medical device acquisition process has moved away from its reliance on emotion toward a basis in fact. As a result, many clinical/biomedical engineering departments have adopted a more comprehensive framework for guiding purchasing decisions. In today’s cash-strapped economy, this represents the business-savvy way to go.

“The demand for capital dollars continues to increase, but the capital budgets themselves have mostly remained the same,” says Heidi E. Horn, vice president, clinical engineering services (CES), SSM Integrated Health Technologies, St Louis. “We therefore need to be smarter about how we spend our capital dollars and cannot afford to waste any of it.”

From the beginning planning stages to final implementation, bringing the appropriate technologies into hospitals—at the right price point—requires much preparation. However, a key question lingers: How can an organization ensure it is selecting the right product for its particular needs?

Narrowing the List

Horn explains that her facility recently approved a new capital planning and allocation policy that spells out specific steps in the clinical equipment purchasing process. First, her CES department determines what equipment may be up for replacement in the next few years. “We identify those devices based on a number of different factors: age, reliability, end-of-service support, clinical needs, recalls, etc,” she says, adding that this clinical equipment replacement prioritization list is published semiannually. Once it is sent to capital decision-makers systemwide, devices can then be incorporated into the capital planning process.

From the beginning planning stages to final implementation, bringing the appropriate technologies into hospitals requires much preparation.

Furthermore, strategic planning teams, physicians, clinical directors, and staff can make clinical device requests, which designated regional capital management teams handle for further review. “Depending on the cost, further approvals at higher levels also may be necessary,” Horn says. “Once the clinical device needs list is analyzed and prioritized, the new policy calls for a systematic and objective process for identifying features that should be included in the purchase. The success of the policy relies on making sure all key stakeholders are involved in all steps of the planning and purchasing process.”

The collaborative exercise is something that Thomas Parnin, CBET, CHSP, director, clinical engineering, emphasizes is very important to St Mary Mercy Hospital, Livonia, Mich, part of the Trinity Health Network. “The ultimate decision [to purchase a product] is a collaboration of all of the stakeholders,” Parnin says. “We would never go to a department and demand that they purchase a specific make and model of the device. What we do is have a collaboration of the stakeholders who get together to figure out what would work best to treat and diagnose our patients.”

With so many options for products in the marketplace, hospitals that take the time to create purchase specifications will support the quest of finding and purchasing the right product with the required functions.

According to Jim Anderson, CBET, CES, director of clinical equipment planning and support and Horn’s colleague at SSM, for large purchases over $200,000 his department uses a weighted score card developed by a project team prior to the request for proposal (RFP). This RFP includes required specifications.

“Purchasing specifications take time and are sometimes difficult to create,” he says. “However, they ensure that you ultimately purchase the best device to meet your needs. Using purchasing specifications can help take some of the emotions out of the decision-making process and allows for the involvement of all key stakeholders.”

In addition to fueling joint collaboration, purchasing specs offer a number of other worthwhile advantages. “One of the key benefits of creating purchasing specifications is it ensures you are doing an apples-to-apples comparison of all manufacturers and models,” Anderson says. “It allows us to more clearly identify the total purchase cost and total cost of ownership.”

Horn points out that the process also helps avoid misunderstandings that may arise between the manufacturer and customer. “It ensures we don’t overlook a necessary component or ‘assume’ something is included in the price or is compatible with our existing systems,” she says. “We have had situations in the past where a vendor alluded that something was included, only to find out that we had to purchase it as an expensive option.”

Parnin’s workplace, which utilizes a five- to six-page universal prepurchase questionnaire, also invests time toward examining utility requirements, whether they are for cotton balls or CT scanners. “The advantages of taking the time to do the research upfront is that we can eliminate any vendor that doesn’t meet the minimum clinical standards,” he says. “That way, we don’t waste each other’s time.”

Purchasing teams also conduct vendor demonstrations and site visits to local install bases to provide users with a sensory experience of a potential purchase.

“You can demo different lights, but you can’t see them in action in the room,” says Robert Bain, MS, CBET, project coordinator, clinical engineering, LifeBridge Health, Baltimore, and president of the Baltimore Medical Engineering Technicians Society. “Sometimes, seeing or putting your hands on the product is much better.”

According to Anderson, a key benefit of creating equipment specs is that it ensures an apples-to-apples comparison of all manufacturers and models.

Parnin agrees, explaining that the visiting team typically includes the end user department, clinical engineering, the ancillary departments that the purchase would affect, and, if there are any possible utility issues, then also facility representatives. “One of the advantages of being a member of Trinity Health, which is a relatively large health care system in excess of 40 hospitals, is that we can reach out to our peers across the country and ask for their experience with certain devices and vendors that are already in place,” he says. “We can take advantage of the fact that the devices that we may be looking at are possibly already in use at another facility.”

Overcoming Brand Loyalty

Although most organizations ideally strive to select medical devices objectively, loyalties to long-time partner manufacturers naturally come into play. “Without a doubt, some people have their favorite vendor,” Horn says. “Even more common, some people have a vendor they won’t even consider based on past experience. Overcoming those biases can be challenging, but are not impossible.”

Because practitioners gravitate toward specific devices, they develop a level of comfort that some may not want to give up. “People have relations with vendors that they like for whatever reason,” Bain says. “There’s nothing underhanded going on. But, for example, some people like Fords, even though the Chevy Camaro is a better car. There’s a brand loyalty. It’s not always wrong, it’s just the way that people are. It’s very difficult to try to get people to get out of the mind-set.”

Also, according to Bain, tendencies exist to lean toward a vendor with which hospitals already have a working relationship because the integration of technologies takes time.

Nevertheless, Anderson maintains it is important that clinical users influence what devices to purchase. “After all, they will be using them every day on patients in their care,” he says.

Along with physicians’ preferences, other factors to consider include standardization, integration and service support needs, existing contractual obligations, purchase cost, and total cost of ownership.

“Each one of these factors should be considered and weighed,” Horn says. “We have found that clinicians and administrators really are open to changing their initial preference if we can show them legitimate reasons why another manufacturer/model may be the better choice—and if their clinical needs are not compromised. Open communication and dialogue through this process is key.”

Ultimately, many clinicians are willing to forgo their biases and learn about the available options. “What we have found is that once they get a chance to evaluate all the other offerings that are out there, sometimes we see that they don’t know what they don’t know,” Parnin says. “Oftentimes, they will reconsider and are open to alternatives.”

Final Decisions

So how is a final decision to purchase usually made? “There’s no rule of thumb,” Bain says. “The worst thing you can do is make a quick decision and hate and regret it later. In all of the places I’ve worked, I can tell you the worst decisions are the ones that are made quickly and on the basis of emotion instead of taking in all the perspectives.”

Parnin also says there is no absolute method for arriving at a particular manufacturer. “As far as who makes the final decision, there is no one person,” he says. “It goes through the collaborative process, and by the time the process is done, upper management is usually willing to authorize the decision that was made by the evaluation team.”

At Parnin’s hospital, once a decision has been made, he makes sure vendors that were seriously considered are notified that they were not selected. Next, the clinical engineering department ensures that the quote received from the winning vendor is up to date. Then, after senior leadership authorizes a request for funds, the equipment is ordered. “Delivery depends on what the device is,” Parnin says. “If we’re talking about a radiology room or CT scanner, we would typically have a lot of infrastructure work that would have to be done, too—coordinated by a project manager. But, if it’s just a manner of buying electronic thermometers, we would say, ‘Get it here as quick as you can.’ “

Before the equipment arrives, infrastructure work and project parameters must be put into place. It is also smart to have applications experts from the vendor come in to make sure users know how to operate new devices correctly.

Bain also suggests other useful actions to employ, saying, “You set up training and service schools for the device. You get a handle on what parts you may need initially to keep the device running and have some of those parts available, like for preventive maintenance, or things that are high-fail, like sensors.”

Lessons Learned

All in all, clinical engineering department involvement in the complex device-acquisition process has proven beneficial across settings. “I think that the most important thing is that clinical engineering is involved throughout the entire evaluation and purchasing process,” Parnin says. “It’s been demonstrated to me that coming in at the 11th hour is not conducive to us getting our needs filled, and the clinical engineering needs are very important.”

Horn says clinical engineering departments need to know how to insert themselves into the clinical device purchasing process, if they have not done so already. “Not only is it now a Joint Commission requirement, the clinical engineering department’s involvement will save capital dollars and ensure the implementation goes more smoothly,” she says. For example, at SSM, some entities involved CES in the decision-making process, while others were not aware of its potential value.

“CES made a concerted effort to ask to be part of those capital review committees,” Anderson says. “In some regions, we were told we could attend the meetings but had no voting rights to approve. As we started pointing out how they could save money, or provided information on the technologies, administration started to trust and value our opinion.” These days, CES is now an active participant on almost all clinical device purchases, and it took on a lead role in the redesign of SSM’s systemwide capital allocation and purchasing policy.

“The end result now is that administration and clinical users seek out CES’ assistance and support and understand we can make their job easier,” Horn says.

Parnin adds that he has long said the clinical engineer’s job also starts at the 13th month. “During warranty, it’s easy,” he says, adding that when the warranty runs out, departments must have a support structure all set to go. “You need to have a contract in place. If you’re going to do a T and M [time and materials], make sure you have the correct testing equipment and tools and service keys already in place. The time to do that is not a week before the warranty expires. The time to do that is well in advance so that by the time the warranty does expire, you can hit the ground running.”

Elaine Sanchez Wilson is a contributing writer for 24×7. For more information, contact .