Three Navy biomeds share their experiences serving in Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Hospital Corpsman First Class (HM1) Eric Ralston, HM1 Ken Gray, and Hospital Corpsman Second Class Ron Welch from Naval Hospital Pensacola (NHP) in Pensacola, Fla, were on their way to a 7-week tour of duty with FH-3 the first-ever Navy medical command to set up an expeditionary medical facility in a war zone during Operation Iraqi Freedom. The $12 million hospital was constructed by a team of approximately 300 medical service support and construction battalion personnel from around the United States.

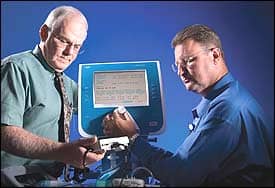

Ralston, who has been in the Navy for 8 years and a BMET for 18 months, says he had no idea that the job of BMET existed when he joined the Navy. It was only after being in the Navy for about 4 years that he heard about it from a friend when he was stationed with the Marines at Camp LeJeune in North Carolina. After being accepted at the Department of Defense BMET school at Sheppard Air Force Base in Wichita Falls, Tex, he took basic and advanced training back-to-back. “I love this job," he says, “It’s the best job I’ve ever had."

Gray has been in the Navy for 19 years and a biomed tech for 16 years. He originally joined the Navy to be an electronics technician, but when he joined, the training was not available. He became a hospital corpsman and trained as a biomed at Fitzsimmons US Army Garrison near Aurora, Colo, which no longer has such a program. “I love my job," he says. “It was a good decision."

Welch has been in the Navy for 20 years. He is retired from the military but hopes to find a biomed position in the civilian sector. He, too, had no idea that BMET school existed when he joined the Navy, but, after having been in for 6 or 7 years, he met several biomeds and was very impressed. He decided to pursue biomedical equipment service and support training at Fitzsimmons and has been a biomed for 8 years.

Setting Up Housekeeping

“The fleet hospital was set up in what used to be an Iraqi air base in the middle of nowhere," says Ralston. “It was all sand everywhere. We started out with big green army tents from about the Korean War age and had to set up 26 of them. We also had TEMPER (tent extendable modular personnel) tents that had about five wings. Additionally, we had expandable shelters about half the size of railroad cars. They folded out like Winnebagos and were connected to the tents by vestibules. Our shop was set up in one of these. A few of the spaces had air conditioning, and we were responsible for maintaining the units. It wasn’t really our job, but we were the only people there who had had any training."

The hospital had initially been set up in a 116-bed configuration, but the crew managed to squeeze in a few more and ended up with 132. Although three shelters had been designated as operating rooms, only two were actually used for that purpose. The third had been redesigned prior to the start of Operation Iraqi Freedom and was used as a clean room with sterilizers, which needed an air conditioned environment.

“The first 3 days were devoted to getting the oxygen generators up and running," Ralston says. “I say generators because the first one broke within 30 minutes. The generators weighed about 6,000 pounds each and were packed in crates called CONEX boxes, so it was not like just pulling a wagon handle. We had to find a 5,000 lb capacity forklift and big chains to pull them out."

“The oxygen generator was our primary responsibility," says Gray. “It was very large: 10 feet tall and 12 feet wide. It sucked in ambient air and put out 93% to 98% medical-grade oxygen. We had to keep the hospital supplied with oxygen, so we had to repair the generator and nurse it along. It was our baby. We had three of these machines and had to use all three to keep one running because of the sand and dirt everywhere.”

Other equipment for which the BMETs were responsible included four portable x-ray units, ECG monitors, defibrillators, critical care monitors (Propaq), all of the OR equipment, anesthesia equipment, and field anesthesia equipment. “We had a portable darkroom," says Ralston. “Basically it was a big black piece of plastic Velcroed to the wall. We literally had to crawl under the plastic to get into the darkroom. It was pretty warm in there. We also had an x-ray room that we never set up because of pollution with the sand."

Once the corpsmen got the oxygen machine up and running and were able to provide oxygen to the hospital, they spent the next 2 weeks getting the other equipment in working order. Ralston reports that he spent 24 hours taking apart three x-ray machines to make two. “During this time," he says, “Welch was babysitting the oxygen generator and Gray was spending time between sterilizers and anesthesia machines and dealing with every other little problem we had. Sometimes we had 48-hour days, but 16 [-hour days] were normal.

Time on Their Hands

Things slowed down after that, and the corpsmen had some leisure time. Welch spent much of his time drawing. “[The sketches] seem to be a popular item here,” he says. “The National Museum of Navy Aviation is going to put them in an archive for me, and they are going to blow some of them up and use them for the Navy Ball."

Ralston says this was when they moved to their side business of removing sand from the CD players, tape players, computers, and equipment of other staff at FH-3.

“Of course, it was free of charge," he says. “We did anything we could do to help the morale of the people we were [serving] with. We made a lot of friends that way.

“The sand destroyed everything. This was not normal sand you would find at a beach here in the States. It had the texture of sifted flour and was in everything. Five minutes after taking a shower, we’d be covered. It was like walking through snowdrifts. Apparently at one time the area was a floodplain that had been dammed off by a previous regime. This made for some very fine, silty sand.”

Rising to the Challenge

When asked about some of the challenges the three BMETs encountered, Welch tells 24×7, “Parts were nonexistent. We got there and we discovered we had no parts whatsoever to fix the equipment. To repair equipment, we cannibalized a lot. Some pieces of equipment that came to us in brand-new boxes were probably 20 years old and broken. We cannibalized them for every part we could get our hands on. We stole fuses and parts from all kinds of equipment—sometimes new equipment. We did anything to keep [the equipment] up and running because we were receiving patients within 3 to 4 days of our arrival. We were fighting a never-ending battle, especially at the beginning. It was horrendous. We had no supplies to start with and had no supply line because we were too far forward."

“The heat was also a problem. The hottest temperature was 145 degrees Fahrenheit. That day we were cooking on top of our isoshelter," Gray says.

Despite the heat, at the beginning of their tour the corpsmen had to wear full MOP gear as protection against chemical, radiological, and/or biological agents. “It was almost like wearing a coat and sweatpants over our uniforms, plus a gas mask and flack jacket. We stayed as close to the air conditioned med repair shop as we could," Gray says.

Helping the Locals

More than 1,100 patients passed through the hospital between April and June. Surgeons performed more than 680 surgeries, sometimes multiple surgeries on the same patients. During the first few weeks, the patients were primarily US and allied troops and EPOWs. After some weeks, that traffic dropped off, and the crew was surprised at how many Iraqis—women, children, families—came to be treated. The locals became the majority of patients.

When asked if they provided training for locals, Ralston says no: “I made one trip from the hospital to a city called Ad Diwaniyah. There was a civilian hospital there that had been damaged during the fighting, and they were trying to get set up so they could begin receiving patients. I coordinated the repair of a C-arm and an x-ray unit[to get the hospital operational].”

“We also supplied the hospital with medications and consumable supplies," Gray says. “We provided IVs, surgical sets, bandages, cleaning items, garbage bags. The motivation was that the sooner we got them up and running, the sooner we could go home. The hospital at Ad Diwaniyah was going to take on the civilians that we had after we left. We spent the last two weeks of our tour working that stuff up along with our supply people." All of FH-3’s other excess supplies and consumables were taken back with the command to Kuwait where it was inventoried and $1 million dollars worth of supplies and consumables were taken to a central location to be used by civilian hospitals in the overall Iraqi relief effort.

Take-Home Lessons

Welch, Gray, and Ralston unanimously agree that their tour in Iraq taught them important things about themselves.

Says Welch, “I believe I can do anything with nothing in no time at all. Before I went [to Iraq], I would complain, ‘I’ve got to wait a week to get these supplies? Dang it! I can’t get hold of the manufacturer.’ Now it’s, ‘Hah! I don’t need that. I can fix this thing with chewing gum and baling wire.’"

Gray echoes Welch’s thoughts, adding, “There is no challenge too great. This is the biggest thing I’ve ever done in my life. The reaction I get from people when I tell them I was there makes me so proud. I am just glad to have served my country with [Welch and Ralston].”

Ralston, too, says one can become an expert on anything if forced to deal with it 24 hours a day. He laughingly says, “Car parts can fix medical equipment, contrary to the manufacturer. You just have to steal the right fuses!"

“I couldn’t have done it without them," Welch concludes. “I wouldn’t have chosen any other people to be there with. Petty Officer Ralston and Petty Officer Gray are the best."

Indeed.

24×7 thanks Rod Duren, public affairs officer, Naval Hospital Pensacola, for arranging our conversation with Petty Officers Gray, Ralston, and Welch. It was a privilege.