?Pop quiz: If you call yourself a clinical engineer, can you assume your role remains constant across international borders?

Answer: Hardly. The duties of clinical engineers (CEs) outside the United States are as varied as the countries themselves. In Japan, CEs work directly with patients as well as equipment, performing kidney dialysis. In England, they help adjust wheelchair configurations as part of patient rehabilitation. In Brazil, as in some parts of the United States, they’re largely relegated to the basement of a hospital performing equipment maintenance, isolated from hospital administrators and discussions about cost control or risk management.

We’re still a long way from obtaining a full picture of the role CEs play in other parts of the world, a problem that largely boils down to communication: although the American College of Clinical Engineering (ACCE) maintains a robust presence abroad, only one international organization devotes itself solely to promoting global collaboration across the field.

The professionals behind the Clinical Engineering Division (CED) of the International Federation for Medical and Biological Engineering (IFMBE) are working to build the international bridges lacking today. Though membership ranges in size from just seven to 10 individuals at any given time, the group is piloting a number of far-reaching projects to gain insight into where the CE field stands today and how it might evolve in the future.

Starting Anew

IFMBE itself is a research-oriented umbrella organization that includes approximately 58 smaller, international associations with an interest in medical or biological engineering. As a federation of associations, it has no direct members itself, but boasts an estimated 120,000 affiliated individuals through its member organizations. Every 3 years, IFMBE associations gather for a World Congress to discuss the latest research developments and enable collaboration. The next will be held in Toronto in spring 2015. (Early registration opens this month.) The following congress is scheduled for Prague, Czech Republic, in 2018.

CED’s elected board includes just one member from the United States: Yadin David, CED’s former chairman and one of the early founders and presidents of ACCE. And among the board’s “co-opted members” and “collaborators”—affiliated membership categories distinct from the elected board—just a handful are Americans. Other members hail from as far afield as Poland, Sweden, Croatia, India, China, and Hong Kong. Saide Calil, CED’s current chairman, lives in Brazil, where he teaches and coordinates a training course to prepare clinical engineers to work in the health market there.

Originally established as a working group in 1979, CED is one of the rare places within IFMBE where individuals, rather than associations, join. It attained official division status in 1985, though its progress thereafter was a bit rocky as the group struggled to maintain its vision. Each CED chairman is appointed by IFMBE and is currently limited by charter to a 3-year term, leading to continuity problems between administrations. (Calil is working to amend the charter to allow appointment of a vice chairman to improve stability.)

In 2009, David stepped in as chairman. Describing himself as “passionate about sharing expertise and knowledge with countries that are just starting to understand how to manage their technology in hospitals,” he got busy renewing the division. David created an organizational framework to allow volunteers to donate time and labor on a part-time basis. Facing the challenge of “how to get a guy from Brazil to collaborate with a girl from India and another guy in Russia and yet have everyone meet at a congress in Europe,” he created a virtual work group using a newly established clinical engineering website. Developed in partnership with Kaiser Permanente (which donated expertise and server space), the site lets users collaborate on projects and review and post comments. Soon after, CED broadcast its first e-meeting from a conference in Germany.

Bridges Abroad

That internal housekeeping allowed the division to begin turning its gaze outward. CED devoted part of its IFMBE-sponsored budget to help fund an ACCE program that has provided hospital equipment management training to more than 60 countries since the 1990s. In 2011, the division facilitated the open translation of the ‘How to Manage’ Series for Healthcare Technology produced by Ziken International. Informally known as the Ziken guides, the series consists of six publications that describe best practices for healthcare technology management.

Since training materials in the developing world can prove difficult and expensive to access, CED collaborated with the Tecnológico de Monterrey medical school in Monterrey, Mexico, to translate the Ziken texts into Spanish. The volumes are available for free download on the IFMBE and World Health Organization (WHO) websites. A Mandarin version was recently completed, and discussions are under way for a French or Arabic translation.

CED also partnered with Orbis International, a nonprofit association that works to prevent blindness worldwide, for a project in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. While Orbis trained surgeons in how to perform cataract surgery, CED representatives trained clinical engineers to ensure the necessary equipment would be functioning properly when physicians needed it.

Many Hands

These days, the group is busier than ever. CED is jointly launching a journal with IFMBE’s Health Technology Division to produce an open access international journal on clinical engineering and health technology assessment. Canadian member Tony Easty is completing a book to help clinical engineers use human factor engineering tools to develop a risk program at their facilities. Like the Ziken translations, the volume will be available for free download on the CED website.

Ernesto Iadanza of Italy is collaborating with David to develop criteria for three international prizes recognizing CEs who contribute to the profession worldwide. Jim Wear, an early founder of ACCE and now retired from the Department of Veterans Affairs, has lent his hand to a number of projects. Calil is working to push forward several initiatives before his term expires in 2015. Those include a survey to generate an international directory of clinical engineers and the development of CED’s own website, an effort he’s undertaking with the help of Fred Hosea, a collaborator member from the United States. The main limitation, Calil says, is manpower. “We need people who will help us.”

One of the biggest challenges remains gathering enough intelligence to assemble resources that help move the entire field forward. Clinical engineers can be shy about putting themselves forward and volunteering their expertise, Calil says. “If we understand how clinical engineers work in Poland, Greece, or Italy, we can then try to set a guide specific to each country, but within the same framework,” he says.

CED wants to compile resources for countries looking to start their own clinical engineering certification programs, something currently offered only in a small minority (including the United States, Canada, China, Japan, and Sweden). Over the next few years, the division plans to build a database identifying the characteristics of existing programs. Mario Medvedec of Croatia is currently working on guidelines to serve as a foundation for initiating a program. One day, CED may endorse certain programs that demonstrate compliance with its protocols, but for now, the division favors letting each nation adapt the guidelines according to its needs.

“Every country has its own particularities. We just give them the basic guidelines, and clinical engineers there will develop the additional requirements,” Calil says.

There’s also talk about establishing a formal curriculum. Practitioners in India, China, Africa, and the United States share overlapping approaches tied to the fields of engineering, physics, informatics, and equipment maintenance. David wants to see to see those essential principles consolidated and documented.

“We in CED would like to at least take this fundamental body of knowledge that is common to everybody and come up with a consensus where we agree that if you want to practice clinical engineering, you must have this type and level of knowledge,” David says. At a recent gathering of CED members in Croatia, David met with representatives of WHO to discuss collaborating on one more initiative: an international training program for disaster preparedness. While giving a presentation on the topic in Dubrovnik, he surveyed the audience to assess what resources are already in place and what tools might be helpful for placement in a virtual database on the CED website.

Although the issue tends to claim higher priority in developed countries, David says preparation is essential regardless of geography or the country’s technological profile. “In Africa, where the needs and conditions are completely different, what they have is very, very critical, and they need to know how to protect it.”

While CED has many directions to head in, one thing is clear: “The more people we have, the more hands to help us,” Calil says. 24×7

Jenny Lower is 24×7’s associate editor. Contact her at [email protected].

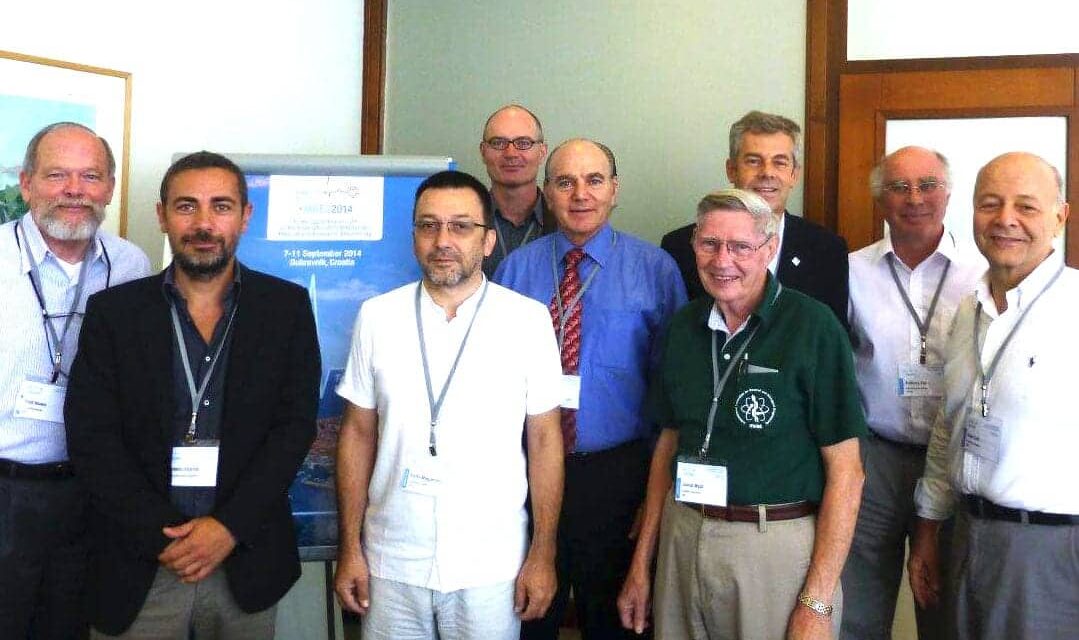

Top Photo: Members of the IFMBE Clinical Engineering Division in Dubrovnik, Croatia. From left to right: Fred Hosea, CED Webmaster, USA; Ernesto Iadanza, Italy; Ratko Magjarevic, IFMBE President, Croatia; Mario Medvedec, Croatia; Yadin David, USA; James Wear, USA; Lago Paolo (guest), Italy; Tony Easty, Canada; Saide Calil, CED Chairman, Brazil.

Thank you collegues for your expertise, dedication and time!

Thanks for your work!

Good to know about CED’s sincere efforts