Cyber security best practices and federal guidelines can steer organizations in the right direction to protect sensitive information

By German G. (John) Baron, CBET, BSBME, CSP

Health care organizations constantly face the challenge of negative impacts incurred with the loss or theft of laptops and mobile devices. The associated risks may range anywhere from financial loss to compromised sensitive patient information, which can result in potential patient safety issues. For this reason, it is imperative that organizations implement laptop and mobile device security policies and risk management programs that follow industry best practices and federal guidelines. In addition, clinical/biomedical engineering and IT departments, in collaboration with other organization team members, must be constantly vigilant for new best practices, technologies, or recommendations that can assist with the reduction of these risks.

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), organizationally located within the Office of the Secretary for the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS),1 cites—on its Cyber Security list—the protection of mobile devices as one of its 10 Best Practices for the Small Health Care Environment. It states that laptop computers, handhelds, smartphones, and portable storage media have opened a world of opportunities, but these also present threats to information security and privacy.2

Because of their mobility, these devices are easy to lose and are vulnerable to theft.

Mobile devices are more likely than stationary ones to be exposed to electromagnetic interference (EMI), especially from other medical devices, such as MRI machines. This interference can corrupt the information stored on a mobile device.

| The associated risks health care organizations face with the loss or theft of laptops and mobile devices range from financial loss to compromised sensitive patient information. |

Because mobile devices may be used in places where others can see the device and view the information on it, extra care must be taken by the user to prevent unauthorized viewing of the protected health information (PHI) displayed on a laptop or handheld device.

Not all mobile devices are equipped with strong authentication and access controls. Extra steps may be necessary to secure mobile devices from unauthorized use. Laptops should have password protection that conforms to that described in the ONC’s first best practice. Many handheld devices can be configured with password protection, and this should be enabled when available. Available, additional steps must be taken to protect PHI on the handheld device, including extra precaution over the physical control of the device, if password protection is not provided.

Laptop computers and handheld devices are often used to transmit and receive data wirelessly. These wireless communications must be protected from intrusion (best practice six describes wireless network protection). PHI transmitted unencrypted across public networks, such as the Internet and public Wi-Fi services, can be done where the patient requests it and has been informed of the potential risks. Generally, however, PHI should not be transmitted without encryption across these public networks.

The Fundamental Risks

The ONC explains that due to the inherent risks of the mobile devices, there must be an overriding justification to store sensitive data that supersedes plain convenience. If it is crucial to do so, then the data should be encrypted. However, if the laptop or mobile device does not support encryption, then it should not be used. The website of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Cryptographic Module Validation Program (CMVP) provides more information about strong encryption.3

Encrypting the data may address the security and privacy issues. However, it does not address the risk of losing the valuable health-related data. As previously mentioned, biomed and IT personnel are constantly vigilant for risk managing improvements. In this case, these teams can consider researching technologies that can provide the clinicians and/or their associates with the capability to upload the sensitive information directly to their own or their associates’ secured servers, instead of storing the data on the laptops/mobile devices. It may be possible to reduce the need for clinicians to store patient-sensitive information on mobile devices by providing these alternatives. One such option is using the PC on a stick technology.

| Reports of IT equipment losses expose the health care organization to negative publicity and may negatively impact patients’ trust. |

This technology provides a methodology for the clinicians to securely access their organization’s network from anywhere in the world with nothing else than a dumb-terminal (laptop without hard drive, personal computer with or without a hard drive) and the PC on a stick. The Air Force and other federal government agencies are successfully using the Air Force Lightweight Portable Security (LPS) to access their respective secured networks. As cited on the Software Protection Initiative Web site,4 the LPS creates a secure end node form trusted media on almost any Intel-based computer. LPS boots a thin Linux operating system from a CD or USB flash stick without mounting a local hard drive. Once booted up, the user directs the browser to his/her network and authenticates using his/her credentials. When the session is finished, there is no trace of the connection and no data left at risk for unauthorized users. In other words, it is a secure and cost-effective option to upload and/or download sensitive information via an encrypted tunnel (such as a virtual private network, or VPN) onto a server instead of storing it in mobile devices.

In addition to the free Air Force LPS, there are vendors who sell their own Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) 140-2 validated PC on a stick versions, available through Web searches.

Secure Kiosks

Another option for clinical/biomedical and IT personnel to consider as a possible method to reduce the need to save sensitive data on laptops is that of setting up kiosks for the organization’s business associates to access their own secured network servers directly from the organization’s health care site. Dedicated VPN kiosks will allow the organization’s business health care associates to upload/download the sensitive data directly from the organization’s site to their secured servers. This will eliminate the need to store the data on laptops and therefore mitigate the risks incurred by the loss of the laptops/mobile devices. The aforementioned options can be part of the organization’s comprehensive laptop risk reduction plan.

The Guide for Applying the Risk Management Framework to Federal Information Systems: A Security Life Cycle Approach (NIST Special Publication 800-37, Revision 1)5 defines risk management as the process of managing risks to organizational operations (including mission, functions, image, and reputation), organizational assets, individuals, other organizations, and the nation, resulting from the operation of an information system. It includes: (i) the conduct of a risk assessment; (ii) the implementation of a risk mitigation strategy; and (iii) employment of techniques and procedures for the continuous monitoring of the security state of the information system. As such, a collaborative approach among all the health care organization’s personnel is essential to abide by its security policies in order to minimize risks to the patients and the organization itself.

A comprehensive laptop risk management plan starts with something that biomeds have excelled at for many years—asset management. Having a thorough inventory of all the laptops used in the health care organization and ensuring that they are configured securely are crucial factors required to minimize negative impacts to the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the patients’ sensitive information. Hence, this writer recommends that the inventory documentation contain the following information at a minimum:

1) Serial number

2) Health care organization’s control number

3) Purpose of laptop

4) Type of information contained (if patient or sensitive information is contained, then security monitoring is of a HIGH priority)

5) Classification (system owner)

6) Method used to secure the laptop (locked

to cart/desk, stored in closet or secured area, monitored 24/7, encryption, etc)

7) Waivers (is the system waivered from having certain security policies?)

After the inventory, risk assessments and privacy impact assessments should be done and documented for each device. NIST provides risk assessment information,6 as well as information for privacy impact assessments.7 The results will assist in categorizing the laptops/mobile devices and prioritizing in order of severe risks to minimal risk impacts.

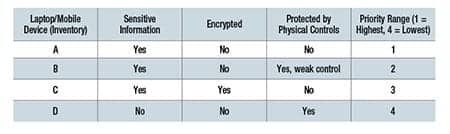

An example of a priority list follows, but it represents a very simplistic example for demonstration purposes only:

Implementing Controls

Now, mitigation controls can be implemented according to priority range. Examples of these controls could include but are not limited to:

1) Hard drive encryption

2) PC tracking (RFID tracking devices)

3) Installed kill signal

4) Installed biometrics

5) Physical security (locked room, tethered,

locked, etc)

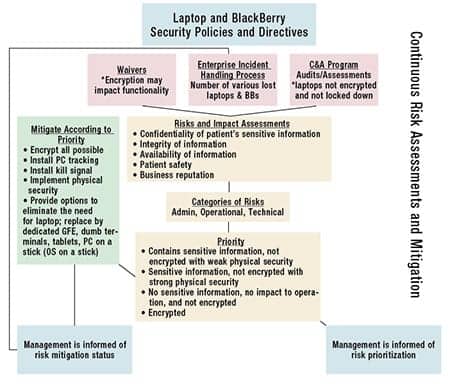

With the collaboration of the health care organization’s information security officer and privacy officer, a facility can implement a continuous monitoring plan that includes compliance and oversight (see the diagram). These officers can periodically review and verify that the appropriate security controls are implemented to minimize the risks. The officers’ documented assessment can be very valuable if the laptop/mobile device is stolen or lost. In other words, the documentation will assist the health care organization to effectively implement an incident resolution process aimed at minimizing the negative impacts to the patients and/or the organization after a laptop/mobile device incident occurs. Such proactive actions serve as strong evidence that the health care organization is doing its due diligence to comply with federal regulations such as HIPAA and Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH).

Reports of IT equipment losses expose the health care organization to negative publicity, HITECH challenges, and ultimately may negatively impact the trust patients have on the institution. Thus, a laptop/mobile device risk management program can assist the organization to promptly and effectively mitigate related incidents. Industries’ best practices and federal guidelines provide excellent resources for the development of such valuable plans/processes. 24×7 February 2013 feature

|

References |

German G. (John) Baron, CBET, BSBME, CSP, has more than 30 years of experience in the biomedical arena, including military medical specialties and clinical experience, and 10 years in the IT security arena. For more information, contact