It may not be surprising to learn that compensation tends to have a heavy weight on the pros-and-cons scales of employees. And it makes sense that more compensation can help to balance a larger workload, while less compensation can lead to less satisfaction. The results of 24×7’s 2010 Compensation Survey provide statistical evidence to support this “common-sense” association.

It is also likely not surprising to learn that biomedical/clinical engineers, specialists, managers, and directors across the United States are busy, though it may surprise some to learn that more of these medical professionals find their workloads acceptable than those who do not. In fact, the great majority of respondents would recommend their profession to others—a fact that is also not likely to surprise them since the “majority” in this instance encompasses 91% of respondents.

In elaborating on a positive recommendation, one survey respondent wrote, “I have always gone home at night with a sense of satisfaction that comes from a job well done. I make a difference. It’s a good career.” Another favorable comment, this one from a New England respondent with an AAS degree, “I love what I do and get a great deal of satisfaction from it. I am in a job where I can have fun, yet challenge myself daily.”

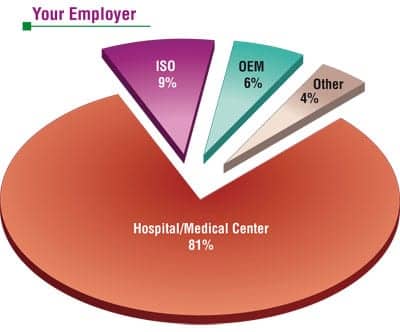

Figure 4. The percentage of respondents by employer type. Other includes home-based care, military, nonprofit, depot services, and education.

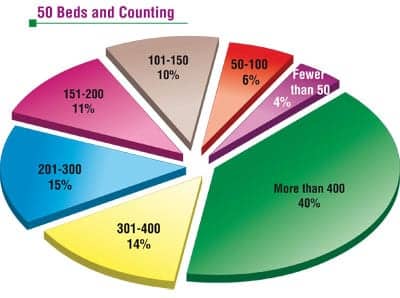

Figure 5. The percentage of hospital employees who responded, per the number of staffed beds.

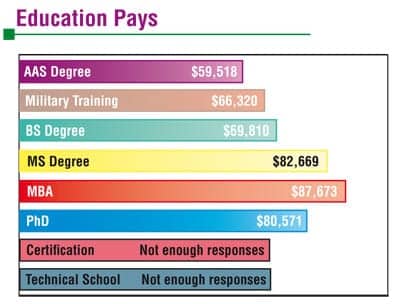

Figure 6. Average salaries of respondents by educational degree or certification (CCE, CBET, CRES, OR CLES).

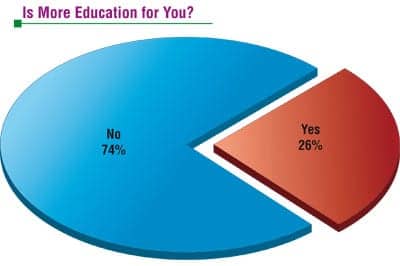

Figure 7. Percentage of respondents who are currently pursuing a formal education.

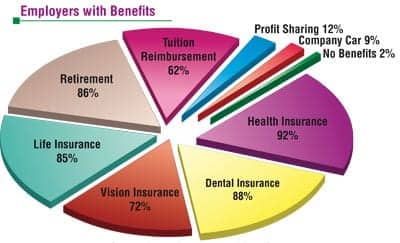

Figure 8. Percentage of respondents who receive each benefit.

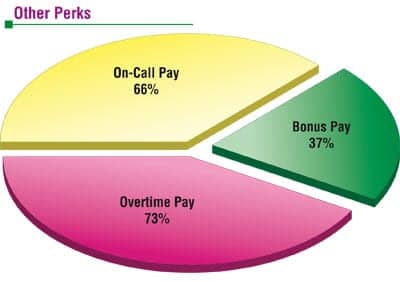

Figure 9. Percentage of respondents who receive each benefit.

Challenge, personal reward, variety, and exposure to new technologies are often cited by survey respondents as positive aspects of their jobs. Of course, there are some negatives as well, mainly focused on inadequate resources, professional limitations, and workload-related stress. One respondent summarized the profession’s dichotomies, writing, “Job satisfaction and security are relatively high. However, like many engineering professions, we still have a mediocre reputation and compensation.”

To counteract an inadequate perception, many clinical engineering departments have sought to enhance their roles in ways that include expansion of responsibilities and increased visibility. Biomeds are now as likely to find themselves involved in committees evaluating new purchases and preparing for construction as frequently as they perform preventive and active maintenance. These new roles have been double-edged swords. While new responsibilities present opportunities to streamline workflows, save money, increase collaboration, and enhance reputation, they also tend to add new tasks to what may already be a busy department schedule. Burnout is a risk. Even those who feel equipped with adequate resources can get overloaded. One clinical engineer employed by an ISO said, “Workload is acceptable. However, the time given during the day to complete my work is not acceptable.”

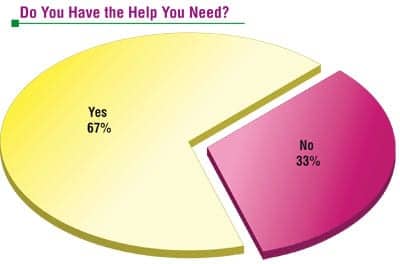

More help would be, well, helpful, but few are hiring. Dollars through attrition, or other money-saving programs, help to boost department bottom lines, but many still would request additional resources if given the opportunity. “I like my job, but the level of costs avoided are poorly understood by upper management. If I had one individual that was saving me half-a-million dollars a year, I would want to make sure he had everything needed to do his job well,” summarized one respondent.

Cash Money

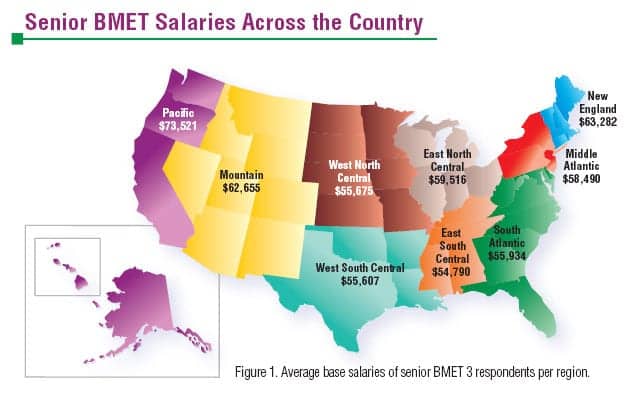

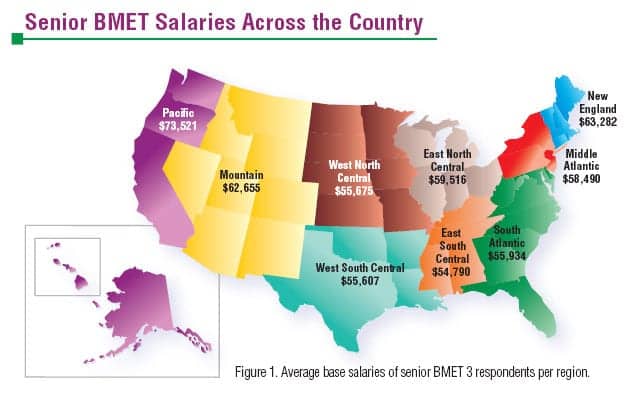

In the current economy, providing ample resources has been a challenge for many institutions, both those within and outside of health care. This has had a mixed impact on salaries. Comparing this year’s numbers for BMET 3s with those of 2009, the trends are geographic. The Eastern Seaboard and East North Central area saw decreases (the Middle Atlantic had the most severe drop at 16%), while the middle and west of the country experienced increases (the largest in the Pacific, with 6.5% growth). The West North Central area essentially maintained. Representing the largest category of respondents, BMET 3s offer one of the best comparative pictures of salaries, with 28% of survey takers reporting this title. Altogether, 1,245 people submitted the questionnaire in full, with a ratio of 92% men and 8% women.

Like last year, the greatest number of respondents work in hospitals and medical centers. “Other,” a small category, includes a broad array of employers, including the government; outpatient dialysis clinics; the military; humanitarian/mission organizations; physicians groups; universities, colleges, and technical institutes; blood banks; durable medical equipment and nursing suppliers; and various specialty clinics.

For Biomed’s Benefit

For many respondents, no matter where they are employed, compensation is not limited to salary. Common benefits, such as bonuses and on-call pay, are specified in the accompanying chart; less common benefits are lumped into the “other” category. This includes items such as stock options, disability, health club memberships, paid time off, pensions, legal services, and parking. A larger portion (1% more) of respondents reported compensation in the “other” category as opposed to last year. This could again reflect the need to balance increasing workloads and decreasing salaries with some type of reward to keep employees satisfied.

One major method is overtime pay. The increase in those receiving overtime increased even more significantly over last year, when only 57% reported overtime compensation. Overtime, on-call pay, and bonuses can definitely make a difference in an employee’s bottom line. Respondents earning overtime or on-call pay reported an additional average of a little over $10,000 in each category; bonuses added an average $12,000 in income annually.

Pay Respect

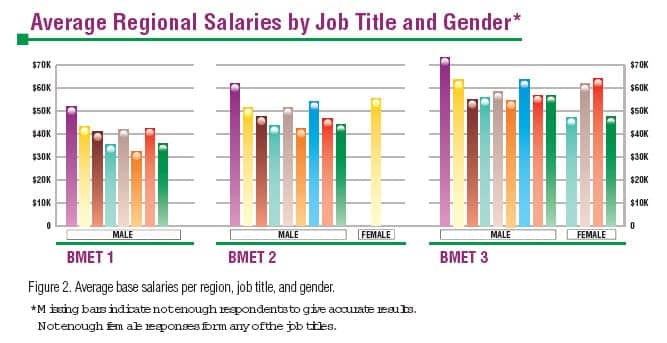

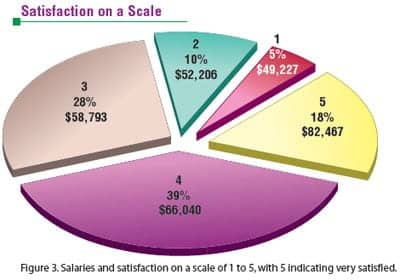

In general, greater compensation leads to greater satisfaction. This holds true across gender and title, on a relative scale, though there are a few exceptions, such as the clinical engineer and the director/executive who are top earners but were the only persons in their category to report the least satisfaction (1 out of 5).

Similarly, a reduction in compensation, whether through salary or benefits, can lead to dissatisfaction, particularly if the work/pay balance is perceived as upended. A female BMET 3 stated, “We have had to work overtime in the past to stay on track for our scheduled preventive maintenance. Now, with the poor economy, we are expected to do the same (and increasing) work without any available overtime. Our compensation is based on pay per performance.”

Those feeling overworked may have the impact aggravated in additional ways, creating even more stress. The same BMET continued, “As a result of our increasing workloads and no overtime, we have been unable to use our vacation time when we would like to use it. If we were to take any vacation time, the large PM workload would not get completed on time, harming our evaluation for potential pay increases.”

Another BMET, this one a male located in the Mountain region, echoes the sentiment, “Corporate America is demanding more time and less pay. I average a 55-hour week and most weekends, and have no time for family or rest. We cannot take more than a week off at a time since most of us are specialists and have no backup to cover our areas of expertise.”

All Work, No Play?

An inability to find the time to take an earned vacation can definitely lead to dissatisfaction with one’s workload, as can many of the other steps health care institutions have been forced to implement in response to dwindling budgets and a tight economy. Cost-cutting measures are commonplace, but many biomeds have chosen to understand; only 2% more of survey respondents over last year reported dissatisfaction with their compensation.

However, there are other areas where biomeds would like to see administrative attention focused. Common complaints regarding workload include unfair distribution among a team; unreasonable responsibilities encompassing both tech and managerial duties; excessive protocol requirements (“I spend more time doing the paperwork than doing checks,” said a BMET 3 in the West North Central region); and a disconnect with administration.

One military-trained CBET would like to see leadership with “a clue about the value we bring to the organization. We are more than an expense eating away [at] the bottom line.” Another CBET, this one located in the Middle Atlantic, responded with a clue for management, suggesting the team would benefit from an “accurate internal equity assessment” that could be applied to help retain properly trained employees.

If the right number of staff is not possible, the right type of resources can go a long way in the support of employees, particularly overburdened employees. An OEM biomed in the South Atlantic region said, “While the workload is exceptionally heavy, my employer compensates me fairly given my education, expertise, and responsibilities. I truly enjoy servicing our customers and being a part of the health care continuum.”

When money isn’t available, the perception of administrative support can help balance an overbalanced workload. Said a female biomed from the South Atlantic, “The workload is tough, but corporate support is outstanding.”

Working Hard for the Money

Many overworked respondents would like to see corporate support in the form of new hires, which can counteract the growing inventories, increasing responsibilities, and expanding campuses common within today’s health care institutions. Nearly three-quarters, or 71%, of respondents reported their facility had no open full-time positions. Many commented about hiring freezes and attrition policies that continue to shrink staff. One CBET with more than 11 years of experience said, “There are not enough techs for the facility. When I started here, the department had four techs. Now we have less with an increased inventory.” Biomeds who have to travel between facilities report being particularly time stressed. A seasoned biomed, also from the South Atlantic region, noted, “Our system is adding facilities to the network and asking us to take care of them even though we are understaffed at our parent facility.”

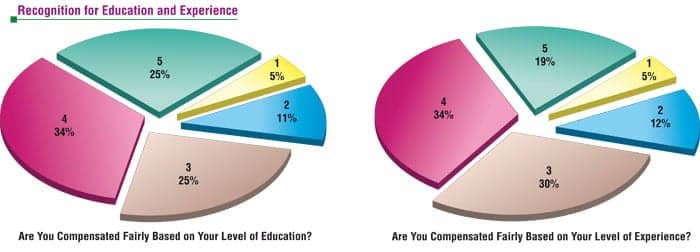

Figure 10. On a scale of 1 to 5 with 5 indicating very fairly compensated, the percentage of satisfaction with compensation, relative to education and experience.

According to one survey respondent, a CBET in the South Atlantic region, industry staffing norms fall around one tech per 1,000 devices and one tech per 100 beds. But many biomeds are asked to handle more. One respondent shared that he is one of two technicians handing more than 4,000 pieces of equipment, and added, “Now the manager has been eliminated and will not be replaced, so one of the techs will also perform most of the manager’s duties.”

These new requirements can be overwhelming for even the most experienced and/or satisfied professionals. One CBET with more than 16 years of experience said, “I can usually handle all requests for service and maintenance in a fairly timely manner. Almost.” Another CBET in the Pacific region said, “Every day engages me to my full potential, but I would enjoy an additional full-time employee.” More aid is a request that many dissatisfied respondents believe would help turn things around, yet few facilities can comply. “We have open positions but are not able to fill them due to a hiring freeze. We have been cutting back on services, trying to identify what services really add value to the institution,” said one biomed with an AAS degree.

Figure 11. Percentage of respondents who feel their workload is or is not acceptable.

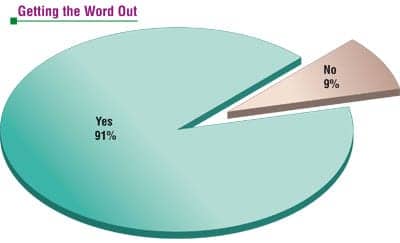

Figure 12. Would you recommend your profession to others?

Smarter workloads and workflows are key to maximizing resources in the clinical engineering department. Respondents are not short of solutions, suggesting improvements in planning, communication, administrative support, tools, training, end user education, flexibility in hours, and different staffing strategies (such as bringing on more BMET 1s, who can take on tasks that free higher-level staff, such as BMET 3s, to handle higher-level work). One respondent, a manager with A+ and CBET certification, went into even greater detail, recommending a “standardized BMET manpower formula and risk-based management technique for no- and low-risk medical devices—eg have those devices on account but loaded with a zero-maintenance PM/CAL/inspection cycle.”

For Love, Not Money

Despite their frustrations, respondents would overwhelmingly recommend their profession to others. This year’s 91% of positive respondents is even greater than last year’s 90% and 2008’s 89%, representing a slow but steady increase. This is good news, since positive recommendations regarding a career choice can help inspire others to pursue it, a potentially important factor in the continuing growth of the field.

Those less likely to suggest a career in the field are unhappy with the compensation (both financial and otherwise), the workload, or both. “The job has become more demanding than ever before with so many added duties. The respect and acknowledgement as to what biomeds do in-house is not well known among staff,” said one survey respondent. Unhappy respondents believe more money can be made and more respect garnered in less demanding careers. “There is too much stress for one person and not enough compensation for the high level of risk involved,” said one respondent.

Most others in the field find the risk worth it. Some enjoy the variety: “I love that you never know what to expect day to day. It’s never boring,” wrote one survey respondent. Others appreciate the challenges: “Every day I get to work with ‘puzzles.’ Figuring out what is wrong with equipment and then repairing it brings about a very satisfying feeling,” said another respondent.

Yet most find reward in the role they play regarding patient care: “You have a lot of responsibility being a biomed, a lot of things to balance in your day-to-day work without much acknowledgement, but the reward is knowing that patients under the care of skilled physicians and nurses are using some top-notch equipment which, hopefully, will reduce their stay and lead to a better experience,” said a respondent.

And some love it all. One respondent summarized neatly: “Biomed rocks! Can do … will do!”

Education as Compensation? Not So Much

Compensation is not always about money. People are sometimes willing to forego a little extra cash for additional benefits or happily work through tight periods with a little exhibited appreciation. Education and training opportunities are excellent ways to provide this reward since they are also often advantageous for their employers, who benefit from the increased knowledge of their employees.

One biomed responding to the 24×7 2010 Compensation Survey stated, “I would like to see AAMI [Association of Medical Instrumentation] promote to health administrators the importance of BMET training and its benefits to the organization.”

Promotion is necessary because education is expensive, and in tight economic times, biomed budgets may not allow for much training. The greatest number of respondents to the survey, 37%, reported no opportunities for training through their employer in the past year, up from 2009 (36%) and 2008 (29%). The remainder were fairly evenly divided among the amount of training received, which ranged from 1 to 20 hours (19%), 21 to 40 hours (21%), and more than 40 hours (23%).

Managers face similar issues with more than two-thirds (68%) reporting no training in the past year. Only 15% attended more than 20 hours of training (17% experienced 1 to 20 hours).

Lacking classroom and lab opportunities, many respondents turn to magazines (33% of respondents reported using these sources for job-related information) and the Internet (40%). Fewer are attending meetings and conferences (15% this year versus 17% in 2009); and a small number utilize journals (8%) and “other” sources, such as vendor and on-the-job training (4%).

Education is key to keeping up with a field that is constantly changing as technology advances. One director in the East North Central region noted, “having the right type of staff with the right attitude, experience, and flexibility is essential to perform the tasks at hand.” So increased promotion of education either from within or outside the individual’s organization would benefit the industry as a whole.

It is definitely beneficial to those working in the profession. One respondent recommends continuing education to all in the field, writing, “Continue to learn new things. Go back to school and learn management, business, and/or networking to supplement your biomedical skills.”

MORE SALARY SURVEY TABLES

Salary by Job Title by Number of Years in the Field by Region

Salary by Job Title by Number of Years with Employer

Salary by Satisfaction with Compensation by Gender

Salary by Satisfaction With Compensation by Job Title

Renee Diiulio is a contributing writer for 24×7. For more information, contact .